Following this brief history of how labor, government, and industry together shaped the American idea of summer, you’ll find a curated list of articles scheduled for publication between now and August 31, 2025. If you’d like full access and want to support The Economic Historian, now’s the time: you can start a 7-day free trial or subscribe for just $30/year—only available for the next 7 days.

A Breathless Hurry

In the early summer of 1869, when the last spike was driven into the transcontinental railroad, economic growth accelerated in the United States, ushering in a new era of national development. And as the economy sped up, so too did the pace of everyday life. “From one year’s end to another,” the New York Times observed, the “sadly overdriven” businessmen of the era lived “for the most part, in a breathless hurry.” If the business-class was entitled to a “summer refreshment,” as the article suggested, the workers toiling in factories and fields were even more so.

In the 1870s, laborers averaged 62 hours a week; by 1890, it had only dropped to 60. Eager for rest, organized workers began calling for “8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will.” While they wouldn’t win the eight-hour day until Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, their picket lines and protests reshaped the nation in surprising ways. As historian Lawrence Glickman shows, labor activists helped popularize the ideas of a “living wage” and an “American standard of living,” which encompassed not just higher pay—but more time for leisure and consumption.

Slower Rhythms

Rather than seeing leisure as a luxury, as many had in previous generations, a growing number of middle-class Americans began to see it as a hard-earned right. Some spent their time after work listening to Len Spencer’s “Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom De Ay” (1891) or Dan Quinn’s “The Band Played On” (1895), while others turned their attention to the weekend. For some, that meant perching on the porch with a penny paper or savoring the slower rhythms of a Sunday afternoon.

Others made their way to the local nickelodeon—movie theaters that charged a nickel to enter a flickering world of fantasy. “This film is exceptionally grand in rich hand-coloring throughout,” an Alabama newspaper wrote of The Red Spectre (1907), a silent horror film—but “the scenes are weird.”

Selling a Season

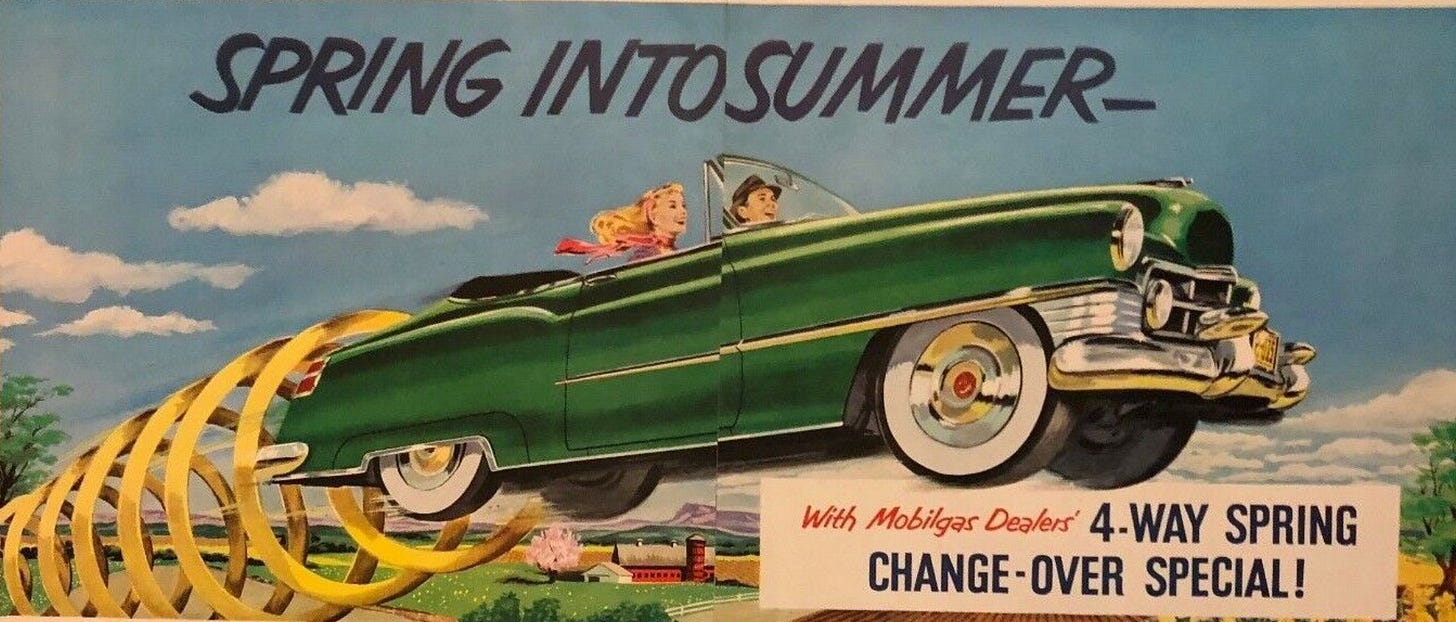

If Americans cherished their weekends, they prized their summers even more. Though many still labored in fields and factories, more middle-class Americans began to see summer as a season of relaxation and travel. In 1907, as Jackson Murphey points out, Kodak began advertising its cameras to tell “the story of a Summer vacation.” By the 1950s, ads made laying in the lawn with a 7Up seem like the “best summer sport there is.”

While American advertisers played a leading role in the long process of constructing an image of summer as a time of leisure and consumption, the U.S. government had a surprisingly significant role as well. During the New Deal, for example, it hired American workers to create camp sites, trails, and swimming pools—many of which last to this day.

Alongside these government programs, the rise of the automobile industry also made it possible for millions of middle-class Americans to take summer road trips to beaches and national parks. “Drive a Chevrolet through the USA,” the actress Dinah Shore sang in a 1953 television ad. While American consumers purchased around five million cars that year, they bought seven million by 1956, the year Congress passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, authorizing the construction of 40,000 miles of a “National System of Interstate Highways.”

Reading into Summer

As Americans hit these new highways in record numbers, many began to buy books and magazines to read when they reached the beach. Magazines such as The Atlantic capitalized on this growing market of readers, publishing sections like “Books the Editors Like.” Teachers and librarians, meanwhile, began curating reading lists for students during their summer break.

What we now call “summer reading” emerged from a long history of leisure—won through labor, shaped by federal policy, and eventually commercialized as a seasonal industry. In that spirit, The Economic Historian offers its own summer reading list: a season-long series of articles on everything from financial panics and the Enron scandal to the history of protectionism, the racial wealth gap, and even the invention of “the economy” itself.

Along with the following list of articles, there will be a few surprise contributions along the way. While some articles will be free, many will be available exclusively to paid subscribers. If you'd like to support the project and gain full access, you can subscribe for just $30 for the entire year—for the next 7 days. After this summer, you’ll receive the fall schedule of articles.

Thank you for supporting The Economic Historian. I hope you’ll enjoy what’s ahead.

Summer Schedule

May 13: The Wright Stuff

Peter A. Coclanis examines the long career of economist Gavin Wright, whose pioneering work redefined how we understand labor markets, racial inequality, and economic development in the American South.

Coclanis is Distinguished Professor of History at the University of North Carolina, and Director of the Global Research Institute.

May 20: Asking Enron Why, 25 Years Later

Gavin Benke revisits Enron’s surreal “Ask Why” ad campaign as a case study in late-1990s business culture, where disruption became dogma, spectacle masked instability, and corporate collapse revealed the ideological limits of the New Economy.

Benke is Senior Lecturer at Boston University.

May 27: China and Poland: The Unexpected Parallels in Economic Development

Marcin Piatkowski examines the surprising similarities in the long-term development paths of China and Poland, revealing how each overcame centuries of extractive institutions.

Piatkowski is Professor of Economics at Kozminski University in Warsaw, and Lead Economist at the World Bank.

June 3: What Isn’t the Economy?

Building on scholars such as Timothy Mitchell and Adam Tooze, historian Johnny Fulfer traces the surprising history of “the economy” as a modern construct, showing how it emerged as a measurable, manageable system—and why that invention still shapes how we think about economic power and policy.

Fulfer is a PhD student in history at Indiana University and the founding editor of The Economic Historian.

June 10: The Power of Patronage: The Medici in Renaissance Florence

Charlotte Moy traces how the Medici family rose from modest beginnings to become Europe’s most powerful bankers, using their wealth to shape art, politics, and empire in early modern Florence.

Moy is Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Alabama.

June 17: When Will There Be an Accounting for Segregation?

Elizabeth Herbin-Triant reveals how Jim Crow was not just a social or legal system, but a sweeping economic regime that extracted wealth from Black Americans through taxes, wages, education, and exclusion—and left a legacy we’ve yet to reckon with.

Herbin-Triant is Associate Professor of Black Studies and History at Amherst College.

June 19: Capitalism, Slavery, and Economic White Supremacy

Calvin Schermerhorn traces the legacy of the 1655 Witte Paard voyage to show how slavery and capitalism grew together in North America—through theft, exclusion, and the systematic denial of Black wealth across generations.

Schermerhorn is Professor of History at Arizona State University.

June 24: Slavery and the Limits of the New History of Capitalism

Phillip Magness examines the NHC’s flexible framing of capitalism and how it obscures meaningful debate on slavery’s economic dimensions.

Magness is a Senior Fellow at the Independent Institute and the David J. Theroux Chair in Political Economy.

July 1: The Monetary Way of War I: The Money Question and the Myth of 1896

Challenging the conventional narrative that the nation’s commitment to gold was a foregone conclusion after the 1896 presidential election, Johnny Fulfer analyzes the nuanced intersections between war, politics, and economic policy, revealing how the Spanish-American War reshaped the nation’s monetary system.

July 3: The Monetary Way of War II: Gold Under Pressure

While many Americans were optimistic about the future of the gold standard after the 1896 presidential election, Johnny Fulfer reveals how the growing tensions with Spain in the months leading up to the Spanish-American War jeopardized this conviction—creating questions about the future of the gold standard in the United States.

July 8: The Monetary Way of War III: Blood, Bonds, and Bullion

Beyond the battlefield, Commodore Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay and the War Revenue Act of 1898 reshaped U.S. monetary politics—bolstering gold reserves and redefining how the federal government raised capital.

July 10: The Monetary Way of War IV: From Manila Bay to Monetary Reform

The passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1900 not only affirmed the United States’ commitment to the gold standard—one of the most important economic institutions in the nation’s history—but it also laid the institutional groundwork for colonial monetary reforms in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

July 15: Women and Wall Street: From Victoria Woodhull to “Fearless Girl”

George Robb traces the long and turbulent history of women in American finance, from Victorian anxieties and Wall Street’s first female brokers to the persistent sexism that still shadows the trading floor today.

Robb is Professor Emeritus of History at William Paterson University.

July 22: The Bank War: How Andrew Jackson Expanded Presidential Power

Michael Trapani explores how the fight over the Second Bank of the United States reshaped American politics, fueled the rise of the Whig Party, and forever altered the power of the presidency.

July 29: How Unions Transformed the Power of Capital into Power for Workers

Sanford M. Jacoby examines how unions leveraged pension fund power to reshape corporate governance, boost organizing efforts, and navigate the contradictions of shareholder capitalism in the post-industrial era

Jacoby is Distinguished Research Professor, Management, History, & Public Affairs at UCLA.

August 5: The Tariff That Divided the Union: The ‘Tariff of Abominations’ and the Nullification Crisis

Heather Michon examines the Tariff of 1828, also known as the “Tariff of Abominations,” which sparked South Carolina’s nullification crisis and set the stage for a constitutional clash over states’ rights, federal authority, and the fragile unity of the early republic.

Michon is a history writer who has contributed to over a dozen encyclopedia and book series for Sage Publishing, Smithsonian Books, and other educational publishers.

August 12: From the Mediterranean to the World: The Life and Legacy of Fernand Braudel

Eric Medlin explores how Fernand Braudel revolutionized the historical profession by shifting focus from political events to long-term social, economic, and environmental forces.

Medlin is a history instructor at Wake Tech Community College.

August 19: The Limited Corporation: A History of Global Capitalism

Kristen Alff challenges Eurocentric corporate history, tracing how Levantine companies shaped global capitalism and resisted incorporation—until legal, cultural, and financial forces standardized the limited liability model.

Alff is Assistant Professor of History at North Carolina State University.

August 26: The Prophet of the Free Market: How Milton Friedman Sold Neoliberalism

Johnny Fulfer examines how Milton Friedman understood capitalism and how he sold it as freedom, becoming neoliberalism’s most charismatic evangelist.