The Wright Stuff

Gavin Wright and the Making of Southern Economic History

By Peter Coclanis

This essay grew out of a conference session honoring Gavin Wright held at the 2024 meeting of the Western History Association in Kansas City, Missouri. At the session, four economic historians—Naomi Lamoreaux, Paul Rhode, Warren Whatley, and I—examined various aspects of Wright’s work over the course of his long career, and Wright offered some remarks of his own. My task at the session was to discuss Wright’s work on the U.S. South since the time of the American Civil War. The author would like to thank Gavin for help with some of the biographical details below.

An Unintended Turn Toward the South

If economic historians were asked to name the scholar who has contributed the most to our understanding of the southern economy, I am quite confident that Gavin Wright would be their overwhelming choice. He took only one U.S. history course as an undergraduate at Swarthmore and “never set out to be a regional specialist,” so it is seemingly ironic that his work has reshaped our understanding of the American South and the field of economic history more broadly.1

Under closer scrutiny, however, irony yields to biography and to “event analysis,” as it were. Not event analysis in a formal social science sense, but in the sense that Wright’s focus on southern economic history reflects what many economic historians would see as path dependency—whereby certain aspects of his background powerfully influenced his intellectual trajectory. Though he has veered off this path from time to time, he has always returned. I am not saying his path was determined in any hard and fast sense—Wright is anti-deterministic by temperament and open to contingency—but there does seem to be a clear pattern in his career, a pattern that grew out of a path established early on.

A few biographical details are needed to demonstrate my point; but first a disclaimer. I first met Wright more than 40 years ago in Charleston, South Carolina at the annual meeting of the Southern Historical Association, where Wright offered a blistering critique of my work. We have stayed in touch intermittently over the years and (despite our first encounter) have a friendly professional relationship, though I can’t say that I know him all that well in personal terms. However, most of the biographical details below come not from my personal recollections but from Wright’s published work, and from a very interesting and informative five-part oral history he did with the Stanford Oral History Program in 2016.2 These sources are sufficiently revealing to allow us to trace—and I would argue help to explain—his principal scholarly path.

The Making of an Economic Historian

Wright was born, auspiciously, in New Haven, Connecticut in 1943. His parents were liberal Quakers with firm commitments to social justice. His father spent his career in various capacities in the social work community, mostly in Minneapolis, while his mother was a teacher. Wright, together withhis three siblings, grew up in a white middle-class neighborhood in that progressive Minnesota city.

After graduating from a public high school in Minneapolis, Gavin went off to college at Swarthmore, an elite Quaker college in suburban Philadelphia. Wright did well there, majoring in economics. At Swarthmore, he was particularly influenced by Joseph Conard, an economist whose “Quaker-based” perspectives proved intellectually and temperamentally appealing. These values presumably included some of those comprising the well-known acronym regarding Quaker values, SPICES: simplicity, peace, integrity, community, equality, stewardship.

Wright was also involved in liberal political activities at Swarthmore, encountering students who were even further to the left. Two of Wright’s most powerful student experiences during this period came not in the classroom or in campus politics, but in summer programs. In the summer of 1963, he participated in a project with the American Friends Service Committee in Warrenton, a small town in the poor, majority black, tobacco-belt county of Warren, North Carolina. Working with a team of students from around the country (as well as a few international students), Wright’s assignment was to increase black voter registration in that small town. A year later, in the summer of 1964, he participated in a skill-enhancement program for underserved youths of all races in the greater Philadelphia area. In towns like Chester, a small city near Philadelphia, the project developed into the Upward Bound program that still exists today. In Chester, Wright deepened a keener appreciation of the role of class in America. And in Warren County, located in the northeastern part of the North Carolina piedmont, Wright encountered the poor rural South for the first time—an experience that sparked questions about race and poverty.

Eager to refine his thinking about economic and social issues and develop analytical tools that would allow him better to explain them, he enrolled in the PhD program in Economics at Yale. In New Haven, he encountered luminaries such as James Tobin, and he enjoyed his general coursework, albeit without any sense of exhilaration.

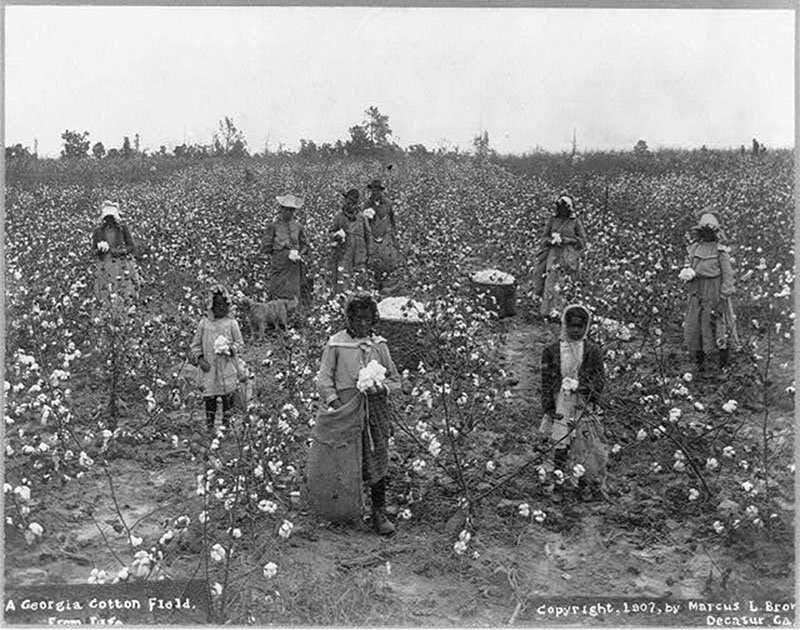

Although he spent a good bit of time in political activism while a graduate student—especially relating to the civil rights movement in New Haven—Wright gradually found his academic footing, first in William Parker’s required course in economic history. He later joined Parker in the summer of 1966 to work on a research project at UNC-Chapel Hill. Along with Parker, Wright also worked with my late colleague, Robert Gallman—the greatest empirical economic historian I’ve ever encountered apart from Paul Rhode. The key deliverable from this project was, of course, the famous Parker-Gallman census sample of the southern cotton economy in 1860. The data proved vital not only to Wright’s dissertation but also to generations of southern economic historians. Though the project wasn’t completed in 1966, Wright’s experience on the project and his engagement with Gallman led him to embrace economic history.

It was in Chapel Hill that Wright’s personal history, interests, values, and temperament came together in a project on slavery and the economy of the Old South. To be sure, the way these factors came together was complicated. He wasn’t seeking to find a linear connection between what he saw and experienced in Warren County, N.C. in the summer of 1963—or the condition of blacks in New Haven in the 1960s for that matter—with the economic history of the South. But he came to see both as fundamentally related in an evolutionary way to the South’s antebellum history and its later status as “a locus of backwardness in the midst of prosperity.”3 And it was with the South’s anomalous economic status in the “Land of Abundance” that Wright devoted much of his professional career. As this essay originated from a conference session that aimed to honor and assess the career contributions of an economist, it was organized, appropriately, via a division of labor. Regarding Wright and the American South, Paul Rhode, who drew first straw, handled Wright’s work on the antebellum period, and I provided commentary on some of his work treating the long period thereafter.

Wright may not have been completely convinced that he had received systematic training in economics at Yale, but he came away from the program with the requisite analytical and technical skills to succeed in the discipline. Working with Parker at Yale sparked a growing interest in southern economic history, which, as suggested above, further developed during his stint in Chapel Hill, but also during a postdoc at the University of Chicago between 1971 and 1972. At Chicago, Wright not only worked with Robert Fogel and his research group examining the economics of slavery, but he also began collaborating with scholars such as Howard Kunreuther, a decision scientist who was also interested in the South. Kunreuther and Wright, of course, went on to produce several thought-provoking articles in the 1970s. In these articles, they sought to explain the complex role of risk considerations in the crop mix farmers produced in the postbellum South.4

Institutions and Inflection Points

While Wright’s work in the 1970s centered around the antebellum period, his collaborations with Kunreuther, his award-winning 1974 essay in the Journal of Economic History, and his last chapter of The Political Economy of the Cotton South (1978), all foreshadowed his later work on the postbellum South. And at the very end of the decade, he turned his attention to the question of labor in the southern textiles industry, which industry began to emerge in its modern form after 1880.5

There were several key takeaways from Wright’s work in the 1970s regarding the postbellum southern economy: the change in the political economy and institutional basis of agriculture due to the war and emancipation; the rise of tenancy and sharecropping; the decline of self-sufficiency among southern farmers; and most important of all, the declining rate of growth in the global demand for cotton, which hamstrung the institutional development of the South for generations. To understand another very important development—the rise of the southern textiles industry in its modern form—Wright emphasizes the quantity of cheap labor in the region, which became especially decisive after 1875.

While still at an early stage in his career, Wright was already demonstrating the scholarly characteristics for which he is justifiably known today. Such as? Detailed empirical research, of course, but also an uncanny ability to spot trends, perceive undervalued developments, ask new questions, and frame clear arguments with boldness and originality. Seen from the standpoint of 2025, it is also fair to say that his early work was generally more formal and technical in nature than his later work.

Though Wright was initially eager to show that he had mastered econometrics and other methods associated with the new economic history, it didn’t overshadow his interest in institutions, historical contingency, and human agency. Indeed, his reception within the historical world was strongly positive at a time when many other economists working in southern economic history were ignored or vilified by scholars trained in history. Wright wasn’t just respectful toward historians; he was also interested in pursuing a mutually beneficial dialogue with them—perhaps another consequence of his Quaker values. This is not to say that Wright should be seen as a kumbaya-type academic promoting harmony at all costs, though his mentor Bill Parker may have been correct in describing Wright as “Gavin the Just” in a memorable book blurb.6 Wright is open and accepting, to be sure, but he isn’t a pushover. He can dish it out when he feels the call, as he has done on occasion—whether writing on the deficiencies of Fogel and Engerman’s Time on the Cross in the 1970s, or those of the new historians of capitalism today. Indeed, as suggested earlier, I was once the recipient of a “rough ride,” as it’s known in police jargon, that Wright initiated long ago. Ouch—it hurt then (and even thinking back on it now), but in retrospect the ride was probably deserved. Maybe “Gavin the Just,” after all.

From Isolation to Integration

Wright has made numerous contributions that have shaped our understanding of the modern South, but one that stands out is Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (1986). Almost forty years after its publication, Old South, New South remains the standard work on the region’s economic history since the time of the Civil War, and it was no surprise that it won the 1987 Owsley Award from the Southern Historical Association, which recognizes the best book on the South. In this study, Wright not only provides a deft summary of the work of other economic historians, but he also fills in numerous gaps in the literature in the service of a bold, strikingly original interpretive intervention into the political economy of the region from the antebellum era through the “long” postbellum era (c. 1865-1930). He not only calls attention to structural changes in the South—revealing a shift in power from labor lords to landlords—but he also reveals the broader political, institutional, cultural, and even moral concerns of this long era. Old South, New South was truly a work of political economy, auguring the renewal of interest in that approach among an increasing number of scholars in recent years.

Insights, large and small, abound in Old South, New South, but most readers would agree on two of the most important takeaways—both related to institutions—that together give structure to the book’s narrative arc. The first takeaway is that the southern labor market was isolated for many decades after the Civil War. This institutional development was reflected and reinforced in laws, policies, standards, and practices that functioned to establish and sustain a low-wage, low-skill, low-productivity regional economy—a “lock-in” mechanism of a sort, in other words. The second takeaway is centered around the powerful institutional role of the federal government during the Great Depression and World War II. The government established and enforced a policy regime that not only worked to boost southern incomes, but also to integrate the southern labor market—a process that finally diverted the isolated and impoverished region from the deeply-rutted and flawed economic path it had long followed.

Most scholars agree that the New Deal initiatives under Franklin Roosevelt reshaped the South, but whether these changes were revolutionary is still being debated. Some scholars, for example, view the changes as occurring more gradually, while others attribute the changes to somewhat different forces; and still others downplay the magnitude of the changes altogether. That said, no one denies that Wright’s focus on institutions and institutional changes that emerged during the New Deal changed the way we think about and periodize the southern economy in the twentieth century.

One can spend hours discussing and debating other questions raised in Old South, New South. Wright’s take on Woodward’s “colonial economy” thesis and Gavin’s provocative argument regarding the fragility of the southern textiles industry—which in his view never had a golden age—are cases in point.Moreover, I know that I’m skipping over other hugely important work, such as Wright’s numerous comparative studies on the textiles industry done in collaboration with Gary Saxonhouse. But space is limited, and Wright’s career has been long, so let us forge ahead.7

Rights and Redistribution

After the publication of Old South, New South, Wright wrote on many different themes pertinent to the modern South, but he devoted more and more of his attention over subsequent years to the confluence of race, economics, and politics. In a sense, then, he was returning—whether as an act of intellectual reversion or scholarly consolidation and career fulfillment—to the themes that originally sparked his interest in studying economics at Swarthmore and Yale.

The principal deliverable from this era of Wright’s work was, of course, his 2013 book Sharing the Prize: The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South, which won the EHA’s Alice Hanson Jones Award for best book in North American economic history. In this monumental study, Wright both reveals the complicated economic, political, social, and institutional factors that expanded economic possibilities in the American South, and demonstrates how these developments shaped the civil rights revolution. While the federal government played a critical role, he also emphasizes the agency of African American activists, who rendered emerging economic and political possibilities into reality. Together, the”feds” and African American activists helped integrate southern labor markets, improve economic outcomes for Blacks, and desegregate schools and public facilities. Along with these efforts, they also contributed to the startling rise in black voting in the South, which materialized in a significant increase in the number of black officeholders in the region. While Wright shows how changing laws were central to this revolutionary era, he also shows how the credibility of governmental commitments to enforce them was equally important. And in an age of considerable Afro-pessimism, it is important to note that in Wright’s view, the civil rights revolution succeeded. Since the 1950s and 1960s, the southern black community has made significant economic, social, and political gains, which did not come at the expense of whites.

In his more recent work, Wright has continued to demonstrate his breadth of vision and empathies regarding black and white southerners. In one particularly interesting thread, he challenged the widespread notion that southern whites immediately and overwhelmingly abandoned the Democratic Party in response to the Civil Rights movement. Instead, he argues that the abandonment process was slow and piecemeal. Instead of an abrupt response to the Civil Rights movement, he shows how globalization and trade liberalization drove many blue-collar whites into the Republican fold, where they remain to this day. Rather than rooting this political shift primarily in racial politics, Wright places more emphasis on the economic factors that left many southern whites asking questions that Republicans seemed to have an answer for.8

A Margin of Hope

We have gained a better understanding from Wright’s analysis of both the South’s political shift to Republican control and the disappointing economic results of the shift. In recent years, Wright points out, we’ve seen stagnating incomes, stagnating communities, and declining public services in many parts of the region.9 But Wright is too open to contingency as a scholar and too committed to liberal ideals to believe that the current situation can’t change again. One source of optimism is the Hispanic population, whose increasingly important economic and political role in the region could be a vehicle of change. After all, there have been precedents before, most notably the powerful changes the South experienced during the Great Depression and World War II—changes facilitated by the federal government, which helped pull the region out the pernicious path it had previously followed. In Wright’s rich scholarship on the American South, then, there is always a margin of hope, even when things seem bleak.

Gavin Wright, “How and Why I Work on Economic History,” in Passion and Craft: Economists at Work, ed. Michael Szenberg (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998), 298.

Gavin Wright, Gavin Wright: An Oral History, Stanford Oral History Collection (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries, 2016), video and audio recordings.

Gavin Wright, “How and Why I Work on Economic History,” in Passion and Craft, 283–303, quote on 298.

Gavin Wright and Howard Kunreuther, “Cotton, Corn and Risk in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Economic History 35, no. 3 (1975): 526–55; Wright and Kunreuther, “Cotton, Corn and Risk in the Nineteenth Century: A Reply,” Explorations in Economic History 14, no. 2 (1977): 183–95; Wright and Kunreuther, “Safety-First, Gambling and the Subsistence Farmer,” in Risk, Uncertainty, and Agricultural Development, ed. James A. Roumasset, Jean-Marc Boussard, and Inderjit Singh (Laguna, Philippines: Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture, Agricultural Development Council, 1979), 213–30.

Gavin Wright, “Cheap Labor and Southern Textiles before 1880,” Journal of Economic History 39, no. 3 (1979): 655–80; and Wright, “Cheap Labor and Southern Textiles, 1880–1930,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 96, no. 4 (1981): 605–29.

For William Parker’s blurb, see Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

Gavin Wright and Gary Saxonhouse, “New Evidence on the Stubborn English Mule and the Cotton Industry, 1878–1920,” Economic History Review, 2nd ser., 37, no. 4 (1984): 507–19; Wright and Saxonhouse, “Two Forms of Cheap Labor in Textile History,” in Technique, Spirit and Form in the Making of the Modern Economies: Essays in Honor of William N. Parker, ed. Gavin Wright and Gary Saxonhouse (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1984), 3–31; Wright and Saxonhouse, “Rings and Mules Around the World: A Comparative Study in Technological Choice,” in Risk, Uncertainty, and Agricultural Development, ed. James A. Roumasset, Jean-Marc Boussard, and Inderjit Singh (Laguna, Philippines: Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture, Agricultural Development Council, 1979), 271–300; Wright and Saxonhouse, “Stubborn Mules and Vertical Integration: The Disappearing Constraint?” Economic History Review, 2nd ser., 40, no. 1 (1987): 87–94; Wright and Saxonhouse, “Technological Evolution in Cotton Spinning, 1878–1933,” in The Fibre That Changed the World, ed. D. A. Farnie and David J. Jeremy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 129–52; Wright and Saxonhouse, “National Leadership and Competing Technological Paradigms: The Globalization of Cotton Spinning, 1878–1933,” Journal of Economic History 70, no. 3 (2010): 535–66.

Gavin Wright, “Voting Rights, Deindustrialization, and Republican Ascendancy in the American South,” Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper Series, no. 135 (November 2020), https://doi.org/10.36687/inetwp135; Wright, “Voting Rights and Economics in the American South,” in Lincoln’s Unfinished Work: The New Birth of Freedom from Generation to Generation, ed. Orville Vernon Burton and Peter Eisenstadt (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2022), 340–88.

David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “The Geography of Trade and Technology Shocks in the United States,” American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 220–25; Autor, Dorn, and Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” American Economic Review 103, no. 6 (2013): 2121–68; Autor, Dorn, and Hanson, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” NBER Working Paper no. 21906 (January 2016), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21906; Wright, “Voting Rights, Deindustrialization, and Republican Ascendancy in the American South,” Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper Series, no. 135 (November 2020), https://doi.org/10.36687/inetwp135.